July 18th 2018

This calm has lasted for 18 hours – so far. It is 1145 and I am sure it started before 1800 yesterday.

I’ve decided that I like calms. There is absolutely no point in getting worked up about them. I cannot make the wind blow and there is no point whatsoever in trying to motor through them – that might work if my destination was ten miles away but currently it is 760 and with a full tank Samsara’s range is only 150 miles.

Besides, the electronic autopilot packed up a few days ago and I am not hand steering a compass course for 150 miles…

So, you might ask: What do you do in an 18-hour calm?

The first priority was some music. I had no idea how much I would miss it but it seems I allowed my phone to go flat and when I charged it up again, Spotify required me to log in again – for which, of course, you need an internet connection.

I deliberated all day about this. I do have an Iridium-Go which gives me satellite access – both to summon help should I need to but also to send blog entries to my son Hugo who is paid £2.50 a time to post them. Theoretically, I should be able to use the same connection to log into Spotify.

Not so; it seems I need an extra app – for which, of course, I require internet access…

I tried a couple of times but, mindful of the $1.25 a minute charge, I didn’t try for too long.

To console myself, I got out the clarinet and played Stranger on the Shore and Londonderry Air but Basin Street Blues sounded terribly forlorn without Louis Armstrong’s Hot Five to play along to.

Then it was time for a cup of tea and a Penguin biscuit. I found that using small tins of evaporated milk caused a terrible mess. In the rough weather of the last few days, I had ended up keeping the can inside a mug so at least I wouldn’t lose the spilt milk. However, that meant the only way to get the can out of the mug was to upend the whole thing – with predictable consequences. Next, I folded a piece of kitchen roll lengthwise and used that to lift it out – but all that happened was that the paper got soaked and disintegrated so not only did I have to upend it all again but I wasn’t even able to use the spilt milk.

Never mind, tea and a Penguin biscuit with Charles Dickens. I was supposed to read him at school and remember thinking “For heaven’s sake, get on with it.” I could hardly blame him, if I was being paid by the column inch, I’m sure I would be just as long-winded (I’m not being paid at all for this. Indeed, if I send it by Iridium, I will be the one who is paying – but I notice that doesn’t seem to stop me going on…)

Actually, I am rather enjoying Pickwick Papers. After all, I have the leisure which I presume Mr Dickens’ readers enjoyed in the early 1800’s. Maybe I’ll get to the end of it. In which case it feels as if I am about to discover a complete treasure trove of delights – after all, those people who appreciate Dickens insist there is nothing like him – people who claim to have read the whole canon twice over…

Of course, after an hour of something like that, I had to return to my own novel-in-progress. Having written one before, I know it’s not as easy as it sounds and I know the process: Just keep writing. Up until now it was all by hand in a blue ring-binder but now I decided I didn’t like the central character – he seemed like a bit of a wimp so I started adjusting him. After covering several sheets with circled paragraphs and arrows pointing in all directions, I remembered how I used to do this: With a pair of scissors and glue. Seeing the film Trumbo, I realised that I was not the only one. Now of course, with Microsoft Word, none of that is necessary.

However, I’ve discovered that writing directly onto a laptop is not as easy on a small boat as it is at my desk at home. I tried putting the laptop on the chart table but that faces forward, meaning I have to brace myself sideways against the lurching of the boat and the mouse keeps running away of its own accord – I have to disable the touch pad because I keep touching it and the cursor disappears Lord knows where.

So, instead, I sit on the windward berth with my feet braced against the leeward with the laptop where it is designed to go – on my lap. Of course, this means I can’t use the mouse and if I disable the touchpad, every time I need to get the cursor out of the document, I have to enable it again.

Well, now I am pleased to report that I have trained myself to keep the heels of my hands on the computer either side of the pad without touching it while my fingers dance across the keys ((I am a touch typist these last 50 years and, as you can tell by the length of this, dancing fingers involves no effort at all).

Once that was sorted, it was time for dinner – the other half of the tin of tuna with sweetcorn. I sweated half an onion with it and added a stock cube to the rice. This cheap easy-cook rice needs much more water but I cut it with 1/4 with seawater and anyway I’m only using three litres a day. Follow that with cucumber and sprouted mung bean salad (always two jars of beans on the go – think I might start a third) and tinned peach slices with as much evaporated milk as I can get into the bowl now I’ve discovered that powdered milk tastes just as good if you let the tea cool or add some cold water first.

Dinner was taken, as usual, at the chart table with the Kindle and Mr Dickens propped up against the compass (to hell with the deviation). I find I don’t miss a glass of wine if I have cold herbal tea instead – using the ship’s mug that Tamsin gave me and I didn’t think would be very practical. It’s made of china and I thought it would get broken in five minutes. But now I think it’s one of the best things on the boat. It’s a pain having to hang onto your drink all the time in case it spills.

Wash up in salt water (but rinse the cups and coffee pot with fresh) then wonder about taking the sails down. They’re slatting away as the boat rolls but they are propelling us in the right direction – albeit very, very slowly. Decide to leave them.

OK, so anyone going nowhere like this would need cheering up. So, how about rewarding myself with a Movie Night. I have about a dozen DVDs and a tiny player which plugs into the laptop. The Bluetooth speaker (no defunct with no music) plugs into the earphone socket and, arranging both sleeping bags into a sort of chaise longue, I watched the RomCom Wimbledon – probably seen it a dozen times but my daughter Lottie and I agree that if you really like a film, you can watch it again and again and always get something new out of it.

There were a couple of intermissions to check for shipping and see if the wind had sprung up. Also, it seemed appropriate to have a small glass of grog – after all, it seemed that the chances of having to rush about on deck were next to miniscule (anyway it was a very small glass).

And so, to bed with the two timers set for 90 minutes – which of course turned out to be pointless since this part of the North Atlantic seems particularly deserted and, no, the wind did not return.

Awoke to rain – and still no wind. Went back to bed.

Finally, when it stopped raining at about 0800, I got up and took the sails down. We were now going very slowly in the wrong direction and there was not enough wind flowing over the windvane to correct this.

Breakfast – made the night before – oats, sultanas and powdered milk allowed to soak overnight. Started the last apple. Chopped it up into tiny cubes to go on top. Perfectly all right, should have bought more.

Remembered I finished the 50/50 sliced bread for lunch yesterday. I brought two loaves with me and now the time has come to start baking. Actually, I really look forward to this. There is nothing, absolutely nothing quite as satisfying as baking your own bread on a long passage – not only the smell or the delight of eating warm bread fresh from the oven but the whole process, watching it rise, seeing it brown…

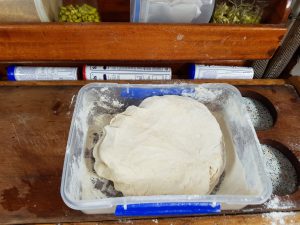

And I have found a very good boat bread recipe:

Take a wide, flat two litre plastic container. Half fill it with strong bread flour. Add two teaspoonfuls of dried yeast.

Make up half a litre of water including one quarter seawater.

Add the water gradually and mix with a metal spoon to a dough. Do not put your hands in it until you can do so without the dough sticking to them.

Light the oven and put it on the lowest setting.

Knead the dough in the container for ten minutes, adding more flour when it starts to stick to your hands. Put the dough on a metal plate and into the oven to rise for ten to twenty minutes depending on the heat of your oven. When it seems to have stopped rising, scrape it back into the plastic container and knead for a further ten minutes. While you are doing this, have the baking tray in the over to warm.

After kneading the dough a second time, shape it into a ball and coat it lightly with flour. Sprinkle some flour into the baking tray. This will stop it sticking. Do not grease the tray.

Return to the oven and allow to rise again. This time, when it seems to have finished rising, turn up the oven to the maximum setting and bake. Check the colour after 20 minutes and then at five-minute intervals.

When it seems to be the right shade of brown, remove from the oven, turn the bread out of the baking tray and allow to cool on a wire rack.

Then enjoy!

…and at last, at 1800 I can report that the calm is over. After lunch of fresh bread, corned beef and pickles with mayonnaise and HP sauce, I decided that enough was enough. The wind was fluctuating between three and five knots from the starboard quarter (or what would have been the starboard quarter if we had been pointing in the right direction) so I hoisted the cruising chute on its own and sat there steering by hand. After a while I reckoned I had the measure of things and carried on with the Pickwick Papers while steering.

This went on for an hour or so, until it seemed we could have the main without it blanketing the chute… we could…

And finally, after an hour of that, I went below and spent the next hour sewing the frayed edge of the ensign – and we were still on course when it was done, slipping gently over a flat sea at about three-and-a-half knots in the direction of Sao Miguel.

It is now 1830. My belief that calms rarely last more than 24 hours is vindicated. I have quite enjoyed it – and now I think we might investigate the beer locker…

____________________

Hi John we didn’t half laugh at the mental picture of you in the buff doing a getting started in norwich