Yarmouth in the old days

Yarmouth today

You never forget your first love – or first job, first car… or the first time you got drunk.

For me, it was in Yarmouth, Isle of Wight, Saturday night, October 24th, 1964.

Yes, that is very precise; for which I must thank my mother, who kept a meticulous sailing diary. I browsed through this recently – and, just as we all yield to the compulsion to look up old flames on Facebook, I was gripped by the desire to return to Yarmouth for a pint (just the one) in the Wheatsheaf.

There was really no other reason to turn right after Hurst narrows – after all, there is a perfectly good anchorage under the castle.

But, in between the Facebook memories, I had been following the outrage at Solent marina prices – and Yarmouth, apparently, is not far behind Beaulieu.

But then a lot has changed in Yarmouth since the 60s.

We had a Sterling in those days – the forerunner of Kim Holman’s Twister – and marinas were not even a twinkle in a developer’s eye. Instead, there were rows and rows of trots and miles of miles of mooring warps to cause endless fun when the boat on inside wanted to leave.

The harbourmaster paddled about in a beautiful varnished rowing boat with impossibly long oars. He never appeared to do any actual rowing but with a pull on one oar or the other, he would spin and hover and ferry-glide to greet his visitors.

I have a notion my father called him “Charlie” while Charlie called Father “Sir” – which was the way things were done in 1964. If Charlie hadn’t been occupied with his oars, I am sure he would have doffed his ancient white-topped cap.

Charlie told you where to go and it was up to you to make the best of it – always with an eye to extricating yourself when the time came to leave. I am sure there were some diffident skippers who berthed on the windward side of the trot and then simply stayed for as long as it took to work their way over to the lee side. It didn’t help that in those days every third boat had a bowsprit.

Now, it’s all different. Now, the whole harbour is filled with the most enormous marina. Of course, there are bigger marinas in the Solent – at Haslar they need a golf cart to rattle around the pontoons checking who’s overstayed. But Yarmouth Harbour is still the same size so I suppose the marina there just seems bigger.

Also, Charlie and his rowing boat have gone. Instead, you call on VHF before entering (nobody had VHF in 1964) and a dory with a big outboard and a man in a baseball cap comes to meet you. Later, I learned there are three of these dories and they don’t just tell you where to go but accompany you, like a tug, to make sure you can get there – particularly if you have neglected the advice to have lines and fenders rigged ready on both sides.

It was while I was sorting out these and quietly drifting sideways that I felt a gentle nudge. The dory had pressed its well-padded bow against mine to straighten me out. It was like having a bow-thruster.

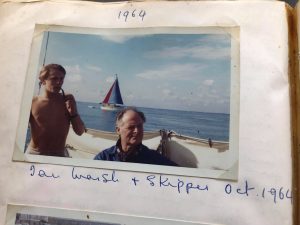

But to return to the story: A Sterling was 28ft – a big boat in those days and, since I was still only 15, my parents felt the need for a bit more muscle on the foredeck. For this, they enjoyed an apparently endless supply of medical students – courtesy of their good friend, the Professor of Rheumatology at the London Hospital.

On this occasion, the volunteer was one Ian Marsh. These days he is probably a respected and retired professor himself and might prefer not to be reminded of what follows (in which case he should stop reading now).

It was after dinner aboard that the future Dr. Marsh suggested we all go ashore. My parents, innocents that they were, saw nothing wrong in this respectable young man taking their 15-year-old to see the sights – after all, he was practically a doctor…

I, on the other hand, had read Doctor in the House and had an inkling of what kind of “sights” these might be. Sure enough, my guide had been to Yarmouth before and was familiar with its quite astonishing number of pubs. As I rowed him in the squishy black Avon Redstart, he announced that we would visit each in turn.

I don’t remember much about it beyond making a great many lifelong friends among the locals whose names I don’t recall now (let’s be honest, I couldn’t recall them the next morning). Certainly, I don’t remember the trip back to the boat or trying to creep aboard without waking the parents.

It turned out we needn’t have worried because while I slept the sleep of the dead (drunk), the future Dr. Marsh crashed about at two o’clock in the morning, stumbling into the cockpit to be sick over the side. Mother said it must have been the tinned salmon.

Restored by a huge fried breakfast, he next announced that we should cut a dash by sailing off the trot and gybing round under headsail. It would be the easiest thing in the world, he said.

My father, never one to refuse a dare, seized on this daft idea. Remember what I said about all those bowsprits? Within half a minute of casting off, I had one foot on someone else’s foredeck and was clawing the headsail down while everyone else gathered in the cockpit to throw warps – all of which landed in the water.

In the end, Charlie wafted over to deliver one of them to a boat on the next trot – something he did without comment. Eventually, we were extricated backwards and without cutting a dash of any sort.

I don’t suppose anybody but me remembers it but still, I was anxious that nothing of the kind should occur this time. Indeed, I stopped the boat an inch from the pontoon and skipped over the side, lines in hand, without so much as a cautious foot on the rail. I certainly didn’t need any thrusting.

Also, I really did have only one pint in the Wheatsheaf – memories of Tobermory are still tender (see “Scotland”, July 15th).

The future Dr Marsh – and my father (who never could refuse a dare).

I have great memories exploring the harbour and helping out Charlie ( or at least I thought I was at the age of 10 !) my memories were that he always sculled his varnished clinker dingy.

His friendship led me to traditional boat building in later years.

That’s interesting. I remember him with two impossibly long oars – although, of course, he never actually rowed – just manoeuvred.

Always Enjoyable reading your stories – most entertaining ! Loved reading your book by the way

Wonderful. John. We must swap Bowsprit stories in Falmouth.

Those were the days. Is it much better now, I am not so sure it is. Once again an interesting story.

Good story, glad you are ok.