This is going to be a “Think Piece”.

A Think Piece – from my old newspaper days – was when something significant happened, and the editor needed to give it the appropriate amount of space but had run out of facts to put in it. All that was left were “Thoughts” – and very often, I was the one who had to think them up – and jolly hard it was, sometimes.

This time, the thoughts came battering at my door. I had just returned from lunch with a pair of long-lost cousins (lost for 20 years and 50 years, respectively – so you will forgive the bottle of wine which I seemed to have all to myself). Anyway, there I was, lying on the bunk attempting to sleep it off when all I could think of was Guy de Boer.

He was a competitor in the Golden Globe Singlehanded Round the World Race. If you’re following this blog, you probably know all about it: The main point is that it is a race without electronic navigation. The competitors have to rely on sextants and compasses and clockwork alarms to make sure they know where they are and stick their head out from time to time to make sure they’re not going to bump into anything.

And last night, 13 days after setting off from Les Sables d’Olonne in western France, American Guy de Boer bumped into the island of Fuerteventura in the Canaries.

It is every solo sailor’s nightmare. Those parts of the internet that pay attention to this sort of thing are alive with pictures of his boat Spirit aground in the surf – alongside comments that everyone is so glad the Spanish rescue service managed to get him off safely. Now there are hopes that the boat may yet be salvaged and sail again.

No one is indelicate enough to ask how it happened – no more than they have asked what were the “personal reasons” that caused fellow competitor Edward Walentoynowicz to retire after less than a week – and that after two years of preparation at the cost of most people’s life savings.

As the remaining 14 skippers press on towards Cape Town and on from there for a total of 30,000 miles (call it somewhere between 200 and 300 days), singlehanders all over the world are thinking: It could have been me.

We all know the golden rule: You work out how far you are from the shore. You calculate how long it would take you to reach it if the wind should change. If your windvane, as faithfully as ever, should turn you in the direction of the rocks. If, come to that, you might even speed up a bit and get there sooner…

So you set your alarm accordingly – and the second alarm in case the first doesn’t work or you just sleep through it.

Then add to this the fact that in the Golden Globe, you don’t know precisely where you are because you don’t have a friendly readout to tell you. Instead, there is just a pencil mark on the chart a couple of hours ago – and that was an update from a couple of hours before that – based on distance and compass course, corrected somewhat haphazardly for leeway and current…

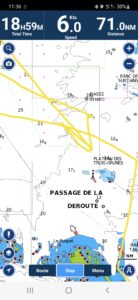

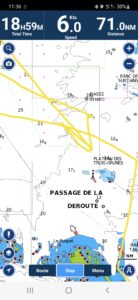

And, be honest, how many of us have woken with our hearts in our mouths, finding ourselves heading straight for the shore? I did it only this week, sailing from Jersey to the Solent. The Navionics track shows me clearly going backwards towards Les Trois Grunes. The boat had tacked herself, the tide was running against me, and I had the alarm set for 20 minutes. OK, so that was plenty. I never came closer than three miles. But what if I hadn’t woken up? What if I had drowsily hit the “dismiss” button on the phone and rolled over, gone back to sleep while the boat – neatly hove-to – slid sideways to disaster?

Foul tide, headwind – and the boat tacks herself while you’re asleep…

What if, for heaven’s sake, I had been forced to rely on a tin alarm clock and thought I had wound it up when I hadn’t – or just set it wrongly? Show me anyone who hasn’t turned up late for work, claiming they slept through the alarm.

Now try telling that to the Spanish Coastguard when your boat is on her side with the breakers pushing her further and further up the beach.

It could happen to any of us. It really could.

Of course, that is the appeal. Who would bother to do this sort of thing if there wasn’t a frisson of danger? It’s like hang-gliding or climbing Everest, or walking across the Arctic. It’s bad enough that the organisers of such races are forced by their insurers to insist on thousands of pounds worth of safety equipment (including two lifebuoys – you’re expected to climb back on so you can throw them to yourself). The competitors have already decided to take the risk.

But I bet they were thinking they would meet their end being pitchpoled off Cape Horn; the boat smashed open by a wave they would hear coming like an express train, the floating container – just falling over the side…

Yet, to run onto a beach after less than 1,500 miles – nobody thinks that is going to happen to them.

The fate of Guy de Boer, a massively experienced sailor who had thought he had covered every eventuality and Spirit, meticulously prepared and ready for anything the ocean could throw at her, just shows that singlehanded sailing and pre-conceived notions make poor bedfellows.

Hi John,

thanks for your great articles, always a good read.

The sheet lead adjusters you call TWINGS were very common on 1960’s racing dinghies – known as ‘ Barber Haulers ‘ – I still use them when required on my Anderson 22 cruiser / racer.

Twings have only got better.

John thanks for the tour and the twing idea. I find the trisail stay very interesting, I have not seen one before, only mast tracks. A Google search did not turn out any usable return. Would you be able to provide some information, as how the top and bottom are connected, length and diameter, and your comments on the usage, etc. Much appreciated.

I’ll write a blog post about it with some photographs. Give me a few days.

John, thanks for your offerings, always a good read. The sheet lead adjusters you call ‘ twings ‘ are also known as Barber Haulers, particularly trendy on 1960’s racing dinghies but I still use them when necessary on my Anderson 22.