A Facebook friend kindly asks to hear about more adventures. How about this one…

I didn’t mean to be out in a Force 9.

That sounds like something out of Arthur Ransome.

But, honestly, in Blood Alley Lake round the back of Poole Harbour’s Brownsea Island, the forecast was for W 5-7 occasionally gale 8. All I had to do was get to Dover and clearly I was going to do it in double-quick time.

It was somewhere south of St Catherine’s Point with half the headsail poled out on one side and two reefs in the main on the other and everything strapped down tight, the log hovering between seven and eight knots, that Solent Coastguard came up with one of their deadpan Maritime Safety Announcements: “Dover, Wight: Westerly severe gale 9 imminent”. Not “possibly” or “occasionally”, you notice. Not “later…”

This would have been all very well; after all, Brighton was a port of refuge. But already it was dark – the kind of dark October night that makes longshoremen shake their heads and stay in the pub – and the entrance to Brighton Marina is no place to be in pitch dark in a Force Nine.

Besides, I had a Rival and, although I am preaching to the converted here, a Rival knows what to do in a Force Nine. She sits down in the sea. She doesn’t leap about but picks her way through the unpleasantness. The only part of the process that is at all inelegant is the size of the bow-wave which would look better in front of a supertanker.

And all the while the Aries carves a series of elongated S-bends through the water, never quite gybing and never quite broaching but just going faster and faster, the harder it blows.

Which was how we ploughed on through the night. Midnight came and went, so did one and two O’clock in the morning. I debated hauling over the lee-board for my ten-minute kips but in fact all was calm and cosy in Samsara’s cabin – almost as if what was going on outside lived only in the met office imagination.

Actually, no: The wind built and so did the sea. By dawn the apparent wind was over 30 knots and I did once see 10.6 on the log as we surfed down a particularly steep wave. Exhilarating, certainly – I was only concerned about how sensible it was. The seas weren’t breaking yet but they were getting very big indeed. Also, it looked as though Samsara might dig her nose into the back of a wave and then I would have green water sluicing down the deck; but that buoyant Rival bow kept on rising. Still, it did occur that, in the open sea, this might be the time for heaving-to.

However, Eastbourne is not Nuku Hiva and suddenly the gap between Dungeness and the westbound shipping lane was beginning to look very narrow indeed. It was a case of gybing or getting the main down altogether. From choice, I would take the wind out of it first but somehow that didn’t seem like an option so, instead, I took a leaf out of the gaffer handbook and de-powered the sail.

Gaffers have a useful technique which goes by the wonderful name of “scandalising”. This involves dropping the peak halyard and lowering the gaff below the horizontal. On a Rival, you can get something like the same effect hauling on the topping so much that the boom sticks in the air like a cockerel’s tail-feather. This makes it possible to stand at the mast and claw down the sail without worrying about being thrown over the side. Now we could bring the wind onto the quarter and dispense with the spinnaker pole. We were still doing seven and eight knots through the water.

The book says to call Dover Port Control two miles off the entrance. I was fairly prompt about this – after all, we were covering a mile every six minutes and there was going to be no chance of “maintaining my position” if a ferry decided to come out.

Meanwhile, I pulled up the binoculars and inspected the entrance. Normally this is a pointless exercise. You can sit at anchor in a stiff onshore breeze and see no sign of breakers on the beach – but try and land in a dinghy and you’ll soon find them.

Looking at the Western Entrance in close-up, the word “maelstrom” came to mind. The gap seemed very small indeed and appeared to be filled entirely with white water.

The tide was racing past so I was going to have to go in sideways which meant heading up into what was now, without any doubt at all, a really “severe gale” even though it might not feel like one with the speed we were doing. If I turned into it with any sail at all, Samsara would go over on her ear and, in breaking water, this might not be good.

Even with a bare pole, would the engine inlet stay submerged long enough to sustain full revs? We were going to need full revs on the little feathering prop too make headway in this.

Look on the bright side. It was quite exciting…

I don’t think I’d ever experienced anything quite like it. Did I say a Rival sits down in the sea? Forget that. In Dover harbour entrance with an onshore Force 9, they get thrown about like a bath toy with a two-year-old who doesn’t want to get out.

To give you an idea of what was going on, the companionway padlock, a great lump of metal which sits in the corner of the cockpit unless I remember to put it away, jumped clean over the side in disgust.

But the engine – worshipful Nanni – kept thundering on and gradually we clawed our way past the end of the northern mole and into what passed for calmer water.

The harbour launch ranged up alongside – rather close, it seemed to me as I clambered about organising warps and fenders. Maybe he had been ready for a rescue.

Just to show what happens when you think it’s all over, I missed the cleat coming into the pontoon and demolished the electricity pedestal. Later, over a calming cup of coffee, I pulled out my phone – something I needed to check…

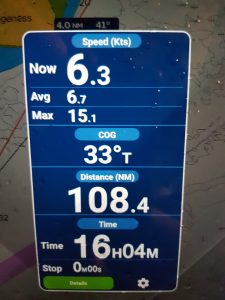

Once I’d got the main down as we came up to Dungeness, I had been astonished at how much calmer everything seemed with just the jib – and yet the log still showed a very respectable 6-7 knots. So how fast had we been going with the main as well?

Navionics has a “Maximum Speed” function if you know where to find it. Of course, it doesn’t account for the tide which had been running at nearly three knots nor the fact that satellite positions sometimes need to catch up with themselves.

Even so, the maximum speed on that memorable overnight passage from Poole to Dover had been 15.1kts.

It’s a record I’m not sure I want to break.