It is about 200 miles from Grenada to Dominica. It took me four days, and I ended up in Martinique.

That’s the good news. It could have been Venezuela.

The other news is that I found the Caribbean Current.

Of course, I knew all about the Caribbean Current. It gets a whole page to itself in the pilot book, which says it travels generally from southeast to northwest and can flow at up to two knots in open water.

“Generally” is the operative word here. The rest of the page seems devoted to saying that nobody is really sure, and you just have to watch out because it can appear almost anywhere at any time, going in any westerly direction, especially between April and June.

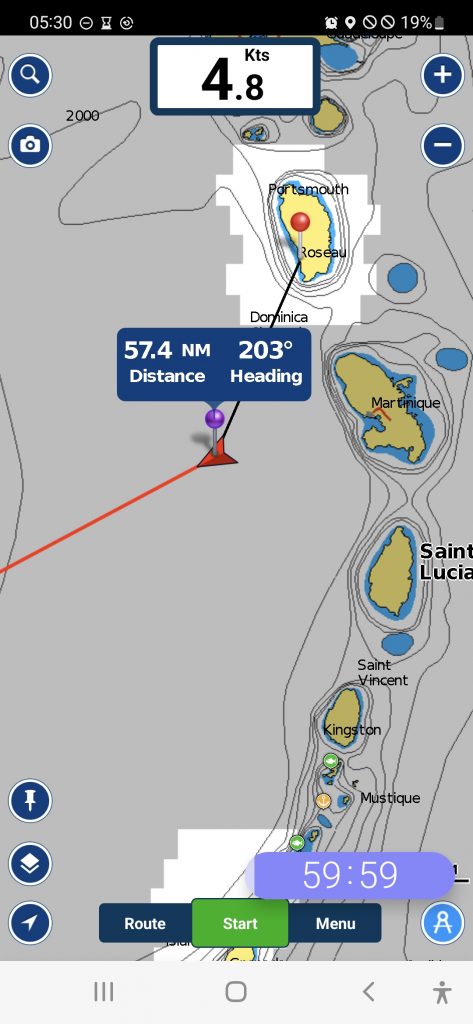

Well, thank you very much. This information I had filed away as mildly interesting and possibly relevant if it happened. Then I woke up at two o’clock in the morning to find the boat becalmed. Out of habit, I looked at the plotter on my way to the cockpit – and was startled to see we were doing 4.8 knots on a course of 203° magnetic.

Now, 203° is southwest. As you can see from the screenshot of Navionics on my phone, there is nothing in the 203° direction until you hit the coast of South America … which is undoubtedly what we would be doing if things went on as they were.

I couldn’t believe it. Where did 4.8knots come from? Nobody mentioned 4.8 knots. I checked both phones. They agreed with the plotter. I took the screenshot in case all of this was some sort of bizarre nightmare, and I would wake up and have to convince myself I hadn’t been dreaming.

Worst of all, when the wind did come back, as it always will, it would be the North-East Trade Wind which – as its name suggests – is from the northeast, and I cannot beat into that and a 4.8-knot current at the same time. I would just go backwards and get very cross doing it.

This was serious stuff. I was 57 miles from my destination in Dominica. I did have 50 litres of diesel, but that would last only about 20 hours hammering away at five knots through the water – and that, I calculated miserably, would give me a speed over the ground of 0.2 knots which would take 285 hours (or put it another way, nearly two weeks).

By that time, I would have to start rationing the water. I forgot to mention this, but I hadn’t filled up before I left. There didn’t seem the need since this was supposed to be just a quick hop up the island chain.

I started the engine – after all, every minute without it put us another cable in the direction of somewhere called La Esmeralda.

The next screenshot shows the situation as we headed for the nearest land – Martinique, 36 miles to the northeast. At our most economical 2,000 revs, you can see the speed over the ground is 0.00kts. In other words, we are standing still. I wound up the throttle to 2,500rpm. At that speed, the little Nanni 21hp guzzles fuel, but there was no point in going nowhere. Gradually the speed over the ground crept up to 0.8kts.

Thirty-six miles at 0.8 knots is 45 hours. We would run out of fuel long before we got there, but my theory was that the nearer we came to the lee of an island, the weaker the current should become. Anyway, 4.8 knots had to be some sort of aberration.

It wasn’t. Or if it was, it was a particularly persistent one. As the sun came up and with it the wind, I still felt as though I was trying to swim up a firehose. Any attempt at sailing sent us whizzing off backwards. The only way to make any progress at all was to keep the nose dead into the current – and, of course, the wind. I put the flattening reef in the mainsail and sheeted it almost dead centre. The headsail was useless, of course.

And then the engine stopped. Within an hour, we were back where we had been at two o’clock in the morning.

It took an hour (in fact, it took three) because not only did I have to change the CAV filter, which looked as though it was full of caviar. In fact, this was diesel bug – something I suffer from particularly because I don’t use the engine nearly enough. The fuel just sits in the tank, growing things.

Also, I don’t inspect the filter often enough. My excuse is that I can never get it back on without it dripping diesel into the bilge. This time I had to re-arrange the seals three times.

The other reason it took three hours was because it wasn’t just the filter that was blocked. The pipe to the tank was full of goo as well. Blowing it out was like volunteering for the trombone section at Beyreuth.

It wasn’t until the middle of the following night that the speed started creeping up – I have never been so pleased to find the boat doing 1kt. The question was: would the fuel hold out long enough to get us into the lee of the island and able to sail again?

Meanwhile, what startled me most was thinking about how this would have played out in the old days before satellite navigation. I wouldn’t have known anything about it until two o’clock in the afternoon and the “midday” sunsight. The morning sight would have given me a position line running northeast to southwest but I would have had no clue where I might be on it until I got the intersect – by which time it would be twelve hours after I had woken up to find the boat becalmed … and another 57 miles in the wrong direction.

I could imagine myself saying: “Sod it: let’s go to South America.”

Of course, in the end, I did make it into Martinique – gradually making more and more progress until l turned off the engine when we were down to the emergency can of diesel for motoring into the anchorage. After that, it was just endless tacking back and forth and gradually creeping closer and closer until the enormous Bay of Fort de France opened out with the “largest and liveliest city in the Windwards” climbing up the hill.

Look on the bright side: I would never have come here if it hadn’t been for the current – in fact, I would never have turned to the Martinique chapter in the book at all – in which case I would not have learned about Diamond Rock just around the corner and how it changed the course of European history.

That’s the best part of pilot books; they tell you stuff you really need to know – in this case, a swashbuckling tale of intrigue and adventure involving Napoleon, Josephine and Lord Nelson – instead of vague predictions about ocean currents.

HI John . Well it just goes to show you can allways learn something new.AS a charter yacht skipper back in the early nineties I have sailed an motored from Granada to St Lucia and St Lucia to Martinique many many times and have never heard of the Carribean currant. Good on you John and happy days.

If you would like to know more about HMS Diamond Rock get in touch. I spent over 20 years sailing the Caribbean in big yachts and did a lot of research into the naval history of the islands.

Wonderful stuff, all thanks to Jeremy Vine 1st lock down.

Blimey what a carry on! That’s as strong as the Gulf Stream! When in those parts in 2016/17 we didn’t notice any current at all. Mind you we had plenty of wind too. Saint Pierre, up the coast is worth a visit. There’s an anchorage there. Portsmouth, Dominica is a lovely spot. Dominica was our favourite island!

It seems everyone says Dominica was their favourite – hence I was trying to get there.

Fascinating